HIV Patients Struggle as Nigerian Hospitals Run Out of Test Kits

Funding cuts by the United States Government have worsened Nigeria’s fight against HIV, as hospitals and clinics across the country face severe shortages of test kits. Despite government promises to increase domestic funding and achieve the goal of ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030, People Living with HIV (PLHIV) continue to feel the impact.

Danladi Adamu, who has lived with HIV for more than 25 years, described the announcement of the funding halt on January 20, 2025, as devastating. Many PLHIV rushed to treatment centres, even on non-appointment days, to secure medications, causing chaos and psychological stress. While antiretroviral drugs remain largely available, the scarcity of test kits has become the most pressing challenge.

Bauchi State NEPWHAN coordinator, Abdullahi Ibrahim, confirmed that test kits ran out in November and remain unavailable. This shortage has slowed community testing and threatens the 95-95-95 global target, which aims for 95% of people knowing their status, 95% of those diagnosed receiving treatment, and 95% of those on treatment achieving viral suppression.

Experts emphasize that testing is the first critical step in HIV care. Dr. Dan Onwujekwe, a TB/HIV specialist, said the lack of test kits reduces access to care and risks spreading the virus further. “If we cannot identify individuals with HIV, we cannot control the epidemic,” he explained.

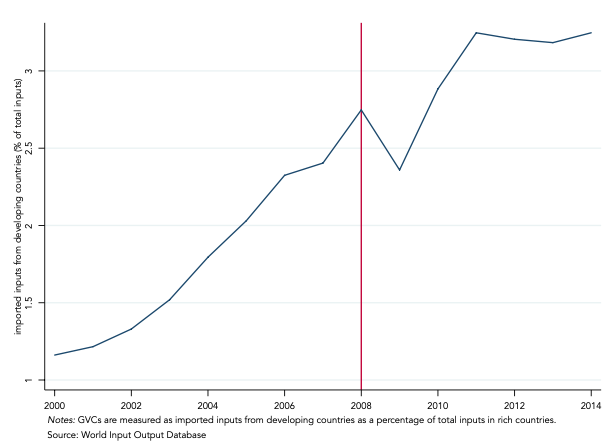

The funding cuts stem from the suspension of the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), a programme that has saved over 26 million lives worldwide. UNAIDS warned that without international support, millions could die or contract HIV, including 1.8 million children at risk by 2040.

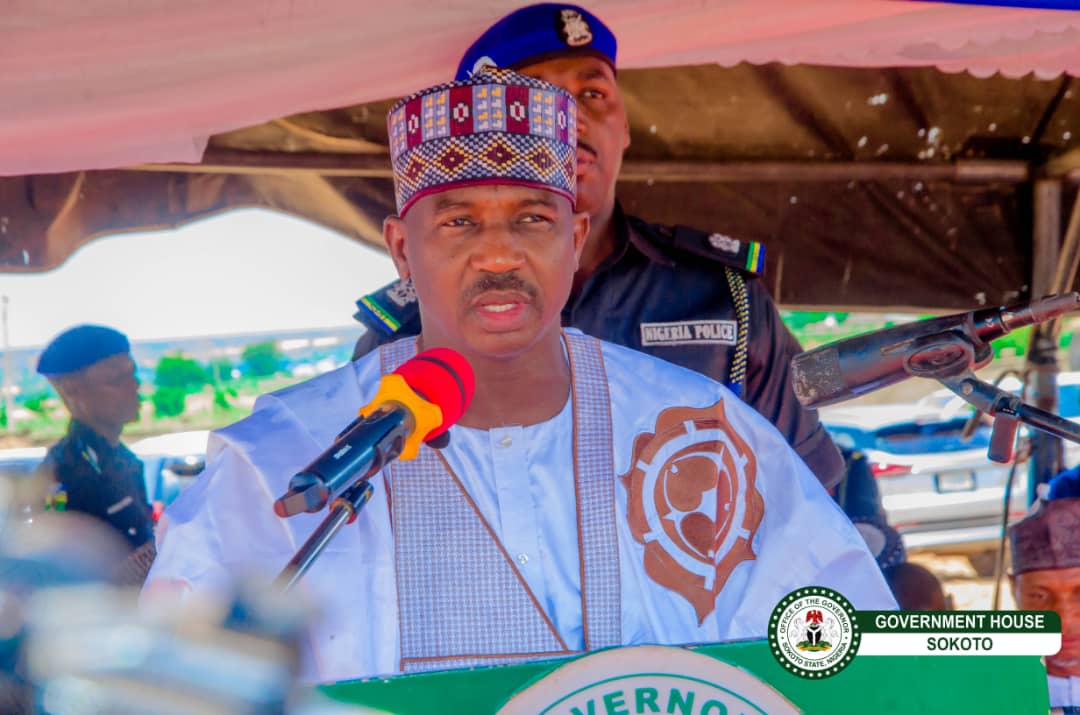

The Federal Government of Nigeria responded with a $200 million intervention fund and launched the Presidential Initiative for Unlocking the Healthcare Value Chain to support local production of antiretrovirals and diagnostic kits. However, PLHIV still face shortages of paediatric drugs, second- and third-line ARTs, and test kits for the general population.

Across the country, the impact varies by region. In the South-East, states like Enugu and Anambra report limited test kits, affecting both community testing and essential monitoring for kidney and liver function. In the South-South, Rivers State faces gaps in community engagement due to the lack of kits, leaving many unaware of their HIV status.

In the North-West, Jigawa State struggles with paediatric ART shortages, while in the North-Central region, the FCT reports difficulty accessing second- and third-line drugs. Outreach activities in Borno and Gombe have also reduced due to limited funding, affecting care delivery to rural and vulnerable populations.

While Lagos State maintains better access to ART and test kits, prevention programmes such as PrEP and care support services have been scaled down, although the state government has stepped in to provide broader access.

Experts warn that continued reliance on foreign aid is unsustainable. Dr. Onwujekwe and Prof. Lawrence Ogbonnaya of Ebonyi State University called for local production of test kits and drugs to ensure Nigeria becomes self-sufficient in HIV care. They stressed that testing is the key to controlling HIV and that persistent funding gaps could reverse decades of progress.

The National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA) has not commented, as its Director-General, Dr. Temitope Ilori, is currently out of the country. PLHIV and advocates continue to urge the government to provide uninterrupted test kits, paediatric ARTs, and support services, to safeguard the lives of millions and sustain Nigeria’s HIV response.